What makes inference...causal inference?

How do we know that x causes y? The straightforward answer is “with a randomized, controlled experiment”. But sometimes the straightforward answer is not possible for reasons of ethical or time constraints. Just think, for example, about trying to set up an RCT on the effect of microplastics on endocrine system disorders. These develop over decades and may want faster answers, and moreover, dosing people with likely harmful substances violates a number of ethical research norms.

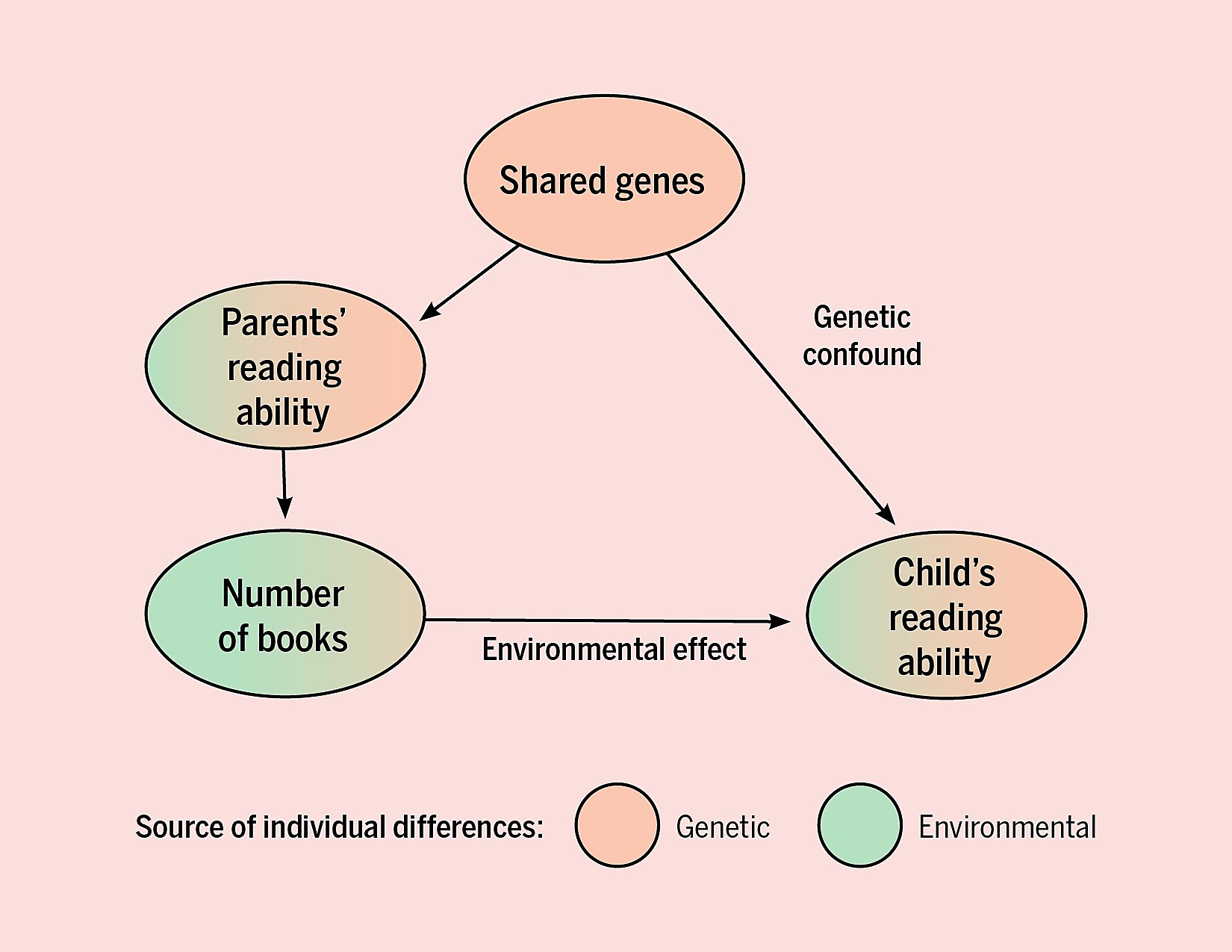

credit: Sara Hart, Callie Little, Elsje van Bergen via figshare.com

credit: Sara Hart, Callie Little, Elsje van Bergen via figshare.com

But the instinct to pursue a randomized, controlled experiment is correct; such a setting ensures that groups being compared are only different in terms of the intervention, on average. We codify this in three major principles of causal inference:

(1) xxx

(2) xxx

(3) xxx

Observational research, where we compare groups with respect to some intervention but subjects were not randomized, complicates getting unbiased effect measurements according to this paradigm. So the trick is to statistically modify our sample to meet these requirements, or to hit upon some great real-world example where this just so happens to be the case–a natural experiment, in other words.

Can we think of a real-world scenario that sets up the experiment for us?

This might be a bit of an idealized example, but it is inspired by ___. Girl Scout cookies are made by two rival baking corporations. One cookie

And if we don’t have a super-clever natural experiment, what are some study design or analytical steps we can take?

Matching

Weighting

Doubly-robust methods